Ski towns are losing what made them special: their year-round residents. Rising home prices, short-term rentals, and the influx of remote workers have driven locals out. This shift has turned vibrant communities into seasonal destinations, replacing neighborly bonds with transactional interactions.

Key takeaways:

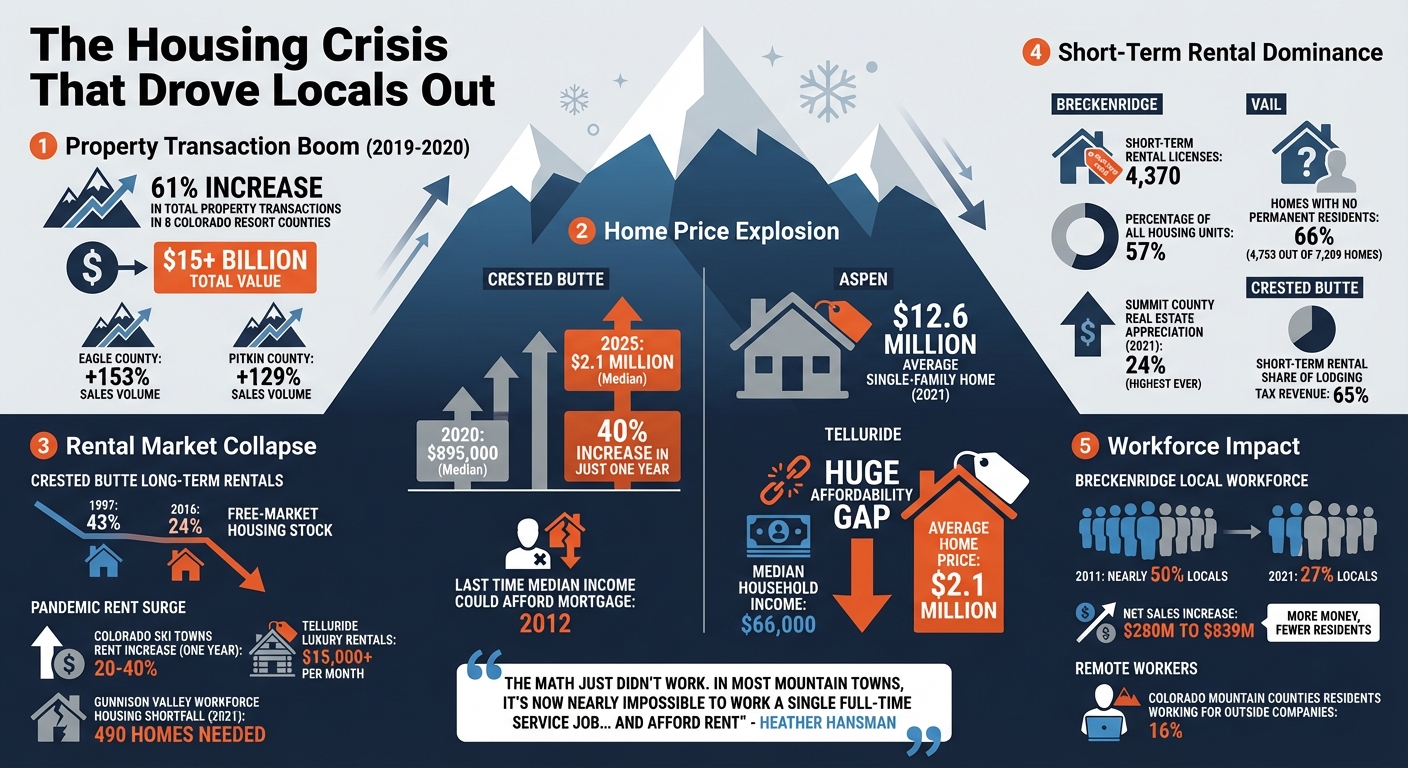

- Housing crisis: Median home prices in places like Crested Butte jumped from $895,000 in 2020 to $2.1 million by 2025, pricing out locals.

- Short-term rentals dominate: In Breckenridge, 57% of homes are now short-term rentals, and in Vail, 66% of homes have no permanent residents.

- Cultural shift: Casual, community-driven traditions have been overshadowed by branded events and luxury pop-ups.

Without locals, ski towns lose their sense of connection and shared identity, becoming polished but hollow versions of their former selves.

Room and Board: Tahoe Housing Documentary (2023)

sbb-itb-236ebff

Who the Locals Were

In ski towns, being a local wasn’t about where you were born - it was about sticking around. Locals were the ones who stayed - the people who kept showing up, season after season. They were lift operators, ski instructors, bartenders, patrollers, and more. They also included teachers, nurses, firefighters, and plumbers - the essential workers who kept these remote mountain communities running. Together, their day-to-day efforts shaped the identity of these towns.

Seasonal Workers Who Stayed

Ski town culture was built by those who returned year after year. It wasn’t the CEOs or property developers who defined these communities - it was the people who stuck around and put in the work. Take Will Dujardin, for example. He came to Crested Butte in 2017 as a 22-year-old ski bum, taking on various jobs like youth freeride coach, house painter, and busser. He even served as Mayor Pro Tem before being priced out of town in 2021. Or Brian Barker, who managed to juggle three jobs - marketing manager for the Adaptive Sports Center, ambulance driver, and videographer - until his rental was converted into a short-term property, forcing him to leave.

These weren’t people who came for a single winter and moved on. They were the ones who gave the town its character, keeping alive the "funky and weird" vibe that made each ski town unique. They knew when a neighbor needed help digging out after a storm, and their small, everyday acts wove the social fabric that made these places feel like real communities - not just tourist hubs.

The People Who Remembered

Then there were the long-timers - people like Glo Cunningham, who has lived in Crested Butte for 50 years. As the outreach coordinator for the town museum and a historical tour guide, she keeps the town’s stories alive. Locals like her remembered when Crested Butte was a coal mining town, long before it became a ski destination. They also carried on traditions like the Vinotok Festival, where the community gathers to perform plays and burn an effigy called "the Grump" to air collective grievances.

This sense of continuity mattered. Former Aspen Mayor Rachel Richards once pointed out that locals weren’t just spectators in the Fourth of July parade - they were the ones marching in it. They coached kids’ sports, volunteered at events, and showed up for free music nights. Their involvement wasn’t about appearances; it came from a deep commitment to their town’s identity. Former town planner John Hess summed it up perfectly: "If we make it nice for us, we’ll make it nice for tourists". Locals weren’t just caretakers of the town - they were its heart, ensuring it remained a living, breathing community, not just a pretty backdrop for visitors.

Why Locals Left

Ski Town Housing Crisis: Key Statistics on Rising Prices and Local Displacement

From 2019 to 2020, property transactions in eight Colorado resort counties skyrocketed by 61%, surpassing $15 billion in total value. Eagle County saw sales volume leap by 153%, while Pitkin County experienced a 129% increase. However, local wages couldn’t keep pace with these soaring prices, setting the stage for a growing affordability crisis.

Housing Became Out of Reach

In Crested Butte, the median home price soared 40% in just one year, reaching $895,000. By 2025, it had climbed to $2.1 million, and the last time someone earning the median income could afford a mortgage there was back in 2012. Aspen saw even steeper prices, with the average single-family home selling for $12.6 million in 2021. In Telluride, where the median household income sits around $66,000, the average home is priced at roughly $2.1 million.

The long-term rental market also took a hit. In Crested Butte, long-term rentals fell from 43% of the free-market housing stock in 1997 to just 24% by 2016. Many property owners realized they could earn in a single week from vacationers what a long-term tenant would pay for an entire month. As housing costs spiraled, service jobs - once the backbone of ski town life - could no longer support the high cost of living. Businesses began cutting hours or shutting down altogether because they couldn’t find workers who could afford to live nearby. This erosion of community participation chipped away at the vibrant culture that locals had long sustained.

Tourism Jobs Couldn’t Keep Up

The economic math simply stopped adding up. As Heather Hansman explained:

"The math just didn't work. In most mountain towns, it's now nearly impossible to work a single full-time service job... and afford rent".

During the pandemic, rents in Colorado ski towns surged by 20% to 40% in just one year. In Telluride, some newcomers were willing to pay $15,000 or more per month for rentals - an amount far beyond the reach of local bartenders, lift operators, or ski instructors. By 2021, the Gunnison Valley faced a shortfall of 490 homes needed to house its workforce. At the same time, a new wave of residents was reshaping the housing market.

The Remote Worker Influx

The pandemic sped up an already building trend: white-collar professionals, now free to work remotely, brought their city-sized salaries to mountain towns. Many of these buyers purchased homes sight unseen, often paying in cash. In some of Colorado’s mountain counties, about 16% of residents now work for companies based outside the region. This influx of remote workers didn’t just visit - they stayed, driving up competition for housing and further squeezing out locals. As Telluride bartender Brianna Anthony observed:

"I feel like Telluride is becoming a community where locals are not welcome but the people who are there six weeks a year, they are welcomed".

In Breckenridge, short-term rental licenses swelled to 4,370, accounting for 57% of all housing units in town. Meanwhile, real estate values in Summit County jumped 24% in 2021, marking the highest appreciation ever recorded. This transformation deepened the housing crisis and reshaped the local job market, while also contributing to the cultural shifts that began with the departure of long-time residents.

What Changed in the Culture

When local residents moved away, the mountains stayed open, and the ski lifts kept running - but something deeper disappeared. That sense of community, once the heart of these towns, began to fade. This loss set the tone for the shifts in social dynamics that followed.

Interactions Became Transactional

Gone are the days of casual drop-ins and friendly chats over a beer. The warm, familiar vibe has been replaced by colder, more impersonal exchanges. Long-time owner-operators who knew their regulars by name have given way to wealthy developers and financiers who often lack ties to the community. In Crested Butte, laid-back, neighborly service has been swapped for upscale establishments catering to affluent tastes. As Telluride bartender Brianna Anthony put it:

"The culture is definitely changing in Telluride. I wonder if these new owners know the dramatic effect they are having".

Community Rituals Faded

Once-vibrant traditions that brought people together have lost their spark. Off-season vacancies now highlight how these events have drifted away from their local roots. In Aspen, for example, the shift in demographics has turned second-home owners into spectators at events like the Fourth of July parade. Meanwhile, the shrinking local population is left to carry the weight of organizing and maintaining these traditions. The locals who used to coach sports, volunteer at events, and support live music are disappearing, taking with them the spirit of community that once defined the town.

Social Accountability Weakened

The erosion of community rituals and personal connections has also weakened the informal social safety nets that once thrived. Michael Yerman, Crested Butte's town planner, summed it up:

"There's a lot to be said for knowing your neighbors and feeling like they have your back when you need it".

But as neighbors are replaced by short-term visitors and homes sit empty for months, that sense of mutual support has all but vanished. Council member Jackson Petito underscored the issue:

"The issue is a town without residents, a town without voters".

Breckenridge town council member Todd Rankin added:

"I don't know how you quantify the cost of losing folks who have been here for a lifetime, but it has an impact".

A 2020 survey of 4,000 residents across Colorado mountain counties revealed that 34% felt their communities’ quality of life was declining. For those who remain, the loss isn’t marked by a single event but by a slow unraveling of connections. Neighbors who once looked out for each other are gone, and interactions have turned into mere transactions. Over time, these changes have transformed ski town culture from a vibrant way of life into little more than a polished facade.

What Replaced the Locals

When year-round residents moved away, the void they left didn’t last long. Instead, it was filled by something entirely different. Over time, commercial forces reshaped the social and cultural landscape of these areas, introducing a new dynamic to what used to be local hubs.

Branded Events Took the Spotlight

Marketing-driven events became the new gathering places. By January 2026, US Ski & Snowboard reported nearly tripling its commercial partnerships, securing long-term deals with brands like Stifel (through April 2034) and Dunkin'. Julia Collier, Chief Marketing Officer of J.Crew, explained why such events resonate:

"Après is social by nature and allows us to tell stories that are true to how people actually experience ski culture, both on and off the mountain."

Seasonal festivals also became a key attraction, boosting visitor numbers at ski resorts by an average of 23% when incorporated into their schedules. For instance, in February 2025, Loon Mountain in New Hampshire teamed up with Red Bull and Frankiebird Productions to host "Red Bull Heavy Metal", drawing over 20,000 attendees to Boston's City Hall Plaza. These events reached beyond traditional ski enthusiasts, engaging audiences who might never have ventured to the slopes.

Short-Term Visitors Dominated

The demographic makeup of these towns shifted dramatically. For example, in Crested Butte, short-term rentals accounted for 65% of lodging tax revenue. In Vail, as of 2016, 66% of homes - 4,753 out of 7,209 - were unoccupied by permanent residents.

This wasn’t just a matter of housing statistics. It fundamentally changed the town’s social dynamics. Streets that were once filled with long-term residents now buzzed with people staying only days or weeks. These visitors came to enjoy an experience, not to put down roots. As communities became more transient, businesses quickly adapted to cater to this new, temporary audience.

Temporary Businesses Became the Norm

Pop-up businesses became a common sight. Take February 2025, for example, when Bemelmans Bar from New York City partnered with Mytheresa to open a temporary location in Aspen. Running from February 14 to March 2, the pop-up targeted après-ski crowds with curated collections from luxury brands like Gucci, Loewe, and Moncler. Heather Kaminetsky, Mytheresa’s North America president, explained the strategy: "meet our clients where they are".

This trend wasn’t limited to fashion. In January 2025, Facegym introduced a "Ski and Sculpt" menu at the Kulm Hotel in St. Moritz, offering facial workouts tailored to combat altitude and harsh weather conditions. Meanwhile, rental platforms like Pickle saw skiwear loans skyrocket by 635% year-over-year by early 2025, alongside a 303% increase in skiwear listings. These temporary services added a touch of luxury and variety, further transforming ski towns into short-term destinations rather than communities for permanent residents.

While the pop-up model proved profitable - helping businesses generate revenue during slower months like January - it also contributed to a more transient, theme-park-like atmosphere. This shift diluted the deeper, long-standing connections that once defined these towns, replacing them with a focus on fleeting, curated experiences.

Why This Matters for Ski Culture

When locals disappear, ski culture shifts from something lived to something consumed. A local leader noted during the town's Fourth of July parade that while second-home owners lined the streets as spectators, it was the dwindling local population that actually participated in the event. Without locals, what once was a shared experience becomes more of a staged performance. This change signals a deeper unraveling of the town's sense of community.

The impact goes far beyond empty storefronts or quieter neighborhoods. True culture thrives on the people who stay - the teachers who coach youth teams, the bartenders who know your favorite drink, the neighbors who help dig you out after a snowstorm. Dara MacDonald, Crested Butte's town manager, captured this sentiment perfectly:

"After a while, it wears on your community when your schoolteachers and folks like that can't be a part of it. They should be the ones coaching and volunteering and showing up for free music. When you drive home for the night and don't come back, it's harder".

Without year-round residents, the threads of community - volunteering, shared presence, mutual support - start to fray. This erosion doesn't just alter daily life; it dismantles the very structures that once held these towns together.

The numbers tell a stark story. In Breckenridge, the percentage of locals in the workforce dropped from nearly 50% to just 27% between 2011 and 2021, even as net sales skyrocketed from $280 million to $839 million. More money poured into the town, but fewer people called it home. Town Councilmember Todd Rankin reflected on the intangible loss:

"I don't know how you quantify the cost of losing folks who have been here for a lifetime, but it has an impact".

What replaces this lived culture is often a polished, surface-level version. Upscale restaurants, curated events, and luxury pop-ups might maintain the illusion of mountain town charm, but they lack the authenticity that made these places special. The quirky, unpolished character - the ski gloves perched on fence posts, the open-door neighborly vibe - gets swapped for something more refined but far less heartfelt. Ski towns risk becoming caricatures of themselves: visually appealing yet empty at their core.

This matters because culture without caretakers loses its meaning. When the people who remember the traditions, who uphold the values, and who create the rituals leave, all that's left is a hollow imitation. It might look like ski culture and sell itself as ski culture, but it lacks the soul that comes from people who stay through off-seasons, invest in the community, and see the mountain as their home - not just a backdrop for a weekend getaway.

Conclusion: Participation Over Consumption

The heart of a thriving ski town lies in its people - those who show up for both the powder days and the community events. As Rachel Richards, Aspen's former mayor, aptly stated:

"We need each other... Once a town loses that balance, it's hard to get it back".

This isn't about pointing fingers or prescribing fixes; it's about understanding. When you visit a ski town, you're stepping into someone else's community - a place where residents work tirelessly to keep the mountain alive, even as the threads of their town's identity start to fray.

True stewardship means being more than just a visitor. It’s about making choices that reflect respect for the community - where you stay, how you interact, and whether you see the town as a vibrant home rather than just a picturesque backdrop. As one local leader put it:

"Show up for stuff and be part of the community, eh?".

Ski towns don’t need rescuing from outsiders - they need acknowledgment and respect. What makes these places special isn’t the polished perfection but the quirky, authentic spirit of the locals who call them home . When participation gives way to mere consumption, all that’s left is a pretty view.

The mountain will always stand, but the culture thrives only through the dedication of its people.

FAQs

How does losing locals affect ski town culture?

When locals move away from ski towns, the entire character of these places starts to change. Locals - whether they’re seasonal workers, lift operators, bartenders, or long-time residents - do much more than just keep things running. They bring history, set the tone, and create the sense of community that gives these towns their unique charm. But when rising housing costs, the boom in short-term rentals, and the pressures of tourism force them to leave, that tightly knit fabric begins to unravel.

Without locals, ski towns can lose their sense of community and start to feel more like commercialized destinations. Instead of a vibrant, lived-in culture, what’s left is often a more superficial experience shaped by visitors, big brands, and one-off events. While these changes aren’t entirely bad, the absence of locals makes it harder for these towns to hold onto the authenticity and spirit that once defined them.

How do short-term rentals impact housing and local culture in ski towns?

Short-term rentals have put a serious dent in the availability of long-term housing in ski towns. This makes it increasingly difficult for locals and workers to find affordable places to live. As a result, housing costs rise, and worker shortages become more common - putting added pressure on local businesses and essential services.

But the impact goes beyond housing. The growing popularity of short-term rentals is also reshaping the character of these towns. With fewer year-round residents, the tight-knit sense of community starts to unravel. The traditions and social connections that locals bring - those little things that make a ski town feel special - begin to fade. While tourists and seasonal events may bring energy, the absence of locals shifts the vibe, making these towns feel more like business hubs than true communities.

Why are remote workers moving to ski towns, and how is it impacting local communities?

Remote workers are flocking to ski towns, drawn by breathtaking scenery, endless outdoor adventures, and the chance to embrace a lifestyle that feels far removed from the hustle and bustle of city life. The shift to remote work, which gained momentum after the COVID-19 pandemic, has made it possible for many to live in these idyllic locations without sacrificing their careers.

But this trend is reshaping local communities in profound ways. The surge in housing demand has caused real estate prices and rental costs to skyrocket, making it harder for long-time residents and essential workers to stay. As locals move out and new arrivals settle in - often without fully immersing themselves in the area’s traditions - the rich ski town culture, once rooted in shared values and a strong sense of community, begins to erode. What was once a tight-knit community risks becoming a destination centered more on tourism than on genuine connection.